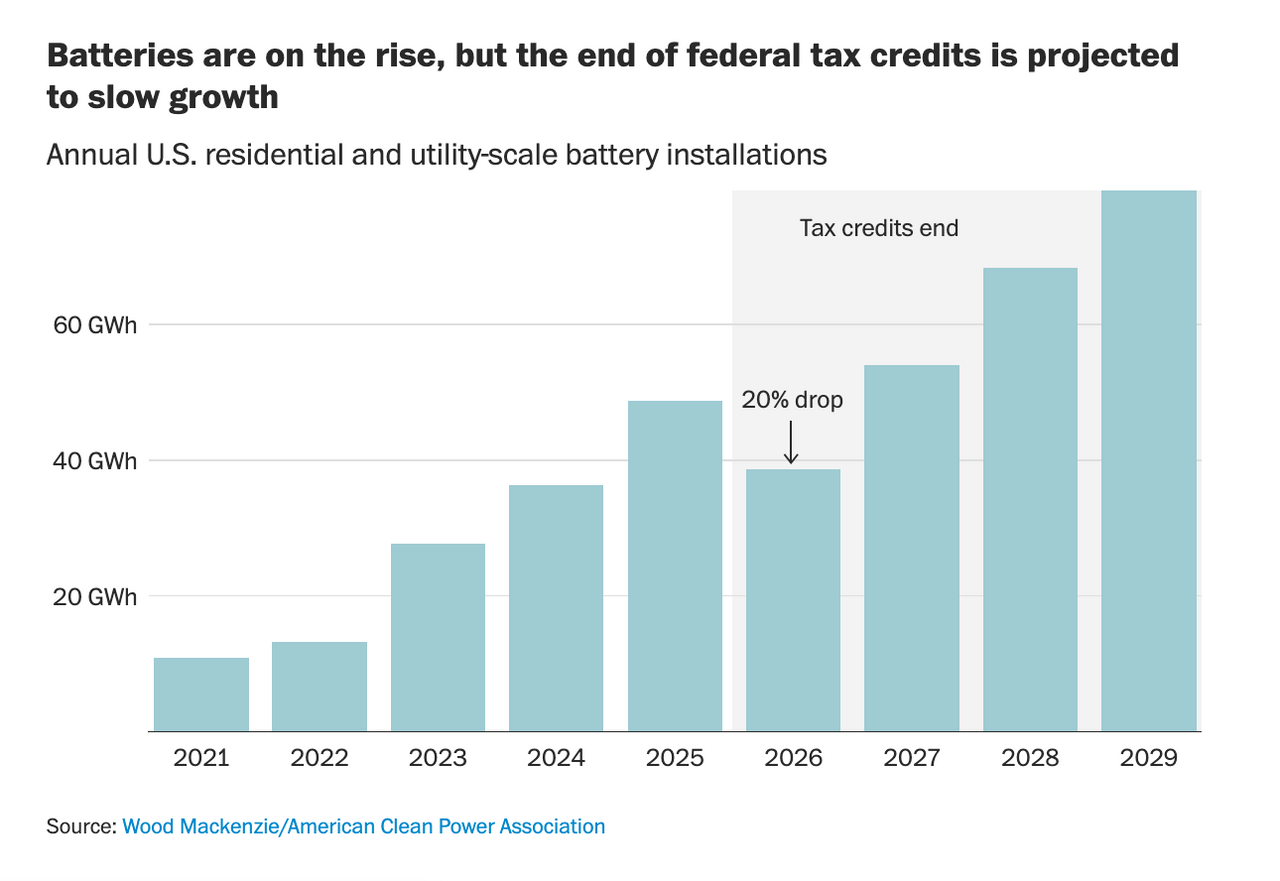

| | | | | Welcome. This week, we have stories on how the medical world relies on horseshoe crab blood and how home batteries are helping to reduce blackouts. But first, my colleague Allyson Chiu writes about how to grow a food forest. | | Hazelnuts are among the food people can pick at the Emerson Street Food Forest in Hyattsville, Md. | | Dawn Taft reached into a tangle of leafy branches, the top half of her body largely disappearing from view. "Oh my God, pawpaws!" Taft exclaimed, holding back large canoe-shaped leaves to reveal a cluster of smooth, light-green fruit. The tree bearing North America's largest native fruit is one of more than a dozen edible plants flourishing in a roughly 8,600-square-foot plot sandwiched between homes and an auto-repair shop. The space in Hyattsville, Maryland, was converted from two empty residential lots about a decade ago. It's now a well-established "food forest" — like a community garden, but featuring food-bearing trees and shrubs, and intended to mimic the natural ecosystem. It provides residents with a chance to harvest fresh, free produce and to connect with nature, said Taft, the city's environmental programs manager and arborist. "When you live in a city, you sometimes don't get to experience the forest," or appreciate that the things you buy from a grocery store were grown somewhere, she said. "That's a really cool piece of what this place offers." Food forest projects have been taking root in multiple U.S. cities. In Atlanta, Boston, Denver, Philadelphia, Seattle and elsewhere, groups have partnered with local communities to cultivate layers of edible plants on public parkland, in empty lots and along roadsides. Their champions say that in addition to food, these forests offer a host of climate and environmental benefits. "It's the most hopeful form of land management that I've heard about," said Lincoln Smith, founder of Forested, a 10-acre experimental forest garden in Bowie, Maryland. Read the full story. |  | Field Sample The horseshoe crabs in the Delaware Bay are the stars of an annual ecological opera involving sex, binge eating and literal bloodlust. Every spring, the crabs clickety-clack ashore for a massive orgy timed to the rise and fall of the tides, depositing millions of eggs in the sand. But conservationists say modern medicine's dependence on a compound in horseshoe crab blood has been upending a globe-spanning ecosystem in which birds bulk up on fatty crab eggs to fuel epic migrations. Now, finally, the crabs have a chance at a reprieve. A key group that sets standards for U.S. drugmakers has officially recognized a human-made alternative as safe and effective, opening the way for pharmaceutical companies to widely adopt alternatives and wean themselves off crab blood. But only a handful of drugmakers have begun to adopt it. Read the full story. | | Two horseshoe crabs on the beach at Bay Point, New Jersey. (Zoeann Murphy/The Washington Post) | Learning Curve The outer bands of Hurricane Erin knocked out power in Puerto Rico this week, becoming the latest storm to batter the territory's aging and fragile grid. By the time this summer ends, the power will go out 93 times, according to a forecast from the island's grid operator, LUMA. But a backup network is helping to minimize blackouts. Roughly 10 percent of homes in Puerto Rico have a battery and solar array. And LUMA, which has agreements with homeowners, regularly calls in the backup batteries to ease shortages in emergencies. The island's experience offers a glimpse into the future for the rest of the United States. As power grids across the country groan under the increasing strain of new data centers, factories and EVs, batteries offer a way for homeowners to protect themselves — and all of their neighbors — from the threat of outages. Read the full story. |  |  | The Second Degree Last week, I wrote about how I tried plug-in "balcony solar," designed for those who can't put panels on their roofs. Many of you were well ahead of me. Josh Spodek, who lives off-grid in New York City, is no stranger to plug-in solar: It's been his only source of electricity for four years. "I was one of the 53 million who couldn't do rooftop solar too," he wrote. "Good old American ingenuity and pluck. Welcome aboard!" Gary K. has had a 400-watt portable system since the '80s. It is mounted on a snowmobile trailer and plugs into an outside socket at his house. "Back then we called it 'Gorilla Solar,'" he wrote. "Plus I can hook up the trailer and take it camping with me!" Douglas Wiest of Wisconsin, who visits Germany every year, wrote that plug-in solar is popular wherever he goes: "Last year, I saw some solar panels on a fence in Gräfelfing, a suburb of Munich, where we stay during our visits." A snapshot is below. |  |  | On the Climate Front From The Washington Post: Global plastic talks collapse after U.S. opposition. A Biden EV charger project is reinvented for the Trump era. A French nuclear plant was shut down by "massive" jellyfish swarm. Some rabbits appear to have tentacles. They're harmless, experts say. From elsewhere: Irreversible climate tipping points approach, the Economist reports. Biodigesters fall short as a climate fix, argues Sentient. Virtual power plants just passed their biggest test yet, reports Inside Climate News. As global EV sales surge, DPA says China is pulling ahead. | | Silvia, 69, sent a photo of her self-designed, 1,000-watt power station at her house. "I am collecting the energy and use it when needed — for a coffee, for cooking, charging my iPhone, starting the ventilator, the router and my little lamps," she wrote. "I keep it all for me, no emittance to the public grid. Easy peasy!" Send me your photos and stories at climatecoach@washpost.com | | Was this email forwarded to you? Sign up here to get The Climate Coach in your inbox every Tuesday. See you next Tuesday, Michael Coren, Climate Coach | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment